WILD AT HEART & OTHER STORIES

(literally me when i bite the hand that feeds me)

-by Katarina Rakušček

July 10, 2025, Moo Deng’s first birthday

About a year ago, I formed a parasocial relationship with a baby hippo.

Reader, I wasn't the only one. Moo Deng, the people’s princess, took the internet by storm. My (admittedly much encouraged) IG discover page was filled with her image: blurred, inexplicably moist, full of rage. “I am just a girl,” she declared in a rosy-cheeked portrait (blush blindness at its best). “Disrespect your surroundings,” she proclaimed in a death-metal edit, emerging from the flames while biting a booted leg, dislocated from its human owner. It was mesmerising. She took over my camera roll, my conversations, and my heart. “Babe, new Moo Deng just dropped,” I hear myself gasping. “Me,” I whisper in bed, bleary-eyed, thirty TikToks in, phone propped against the bedframe. Je suis Moo Deng.[1]

We exchange the endless supply of hippo memes with friends. We know, for sure, this is a capital G girl, not because of her biological sex or her social gender, but rather due to her aesthetic function. We know, in an intuitive and in a cerebral way, that the girl has long abandoned its human form, and as the shapeshifter she is, she constantly looks for new bodies to inhabit: Godzilla. Moo Deng. Flix Bus. The Ocean. Her representational fluidity is what makes her so attractive, subversive and reactionary at once, the ultimate decoy. I look to Alex Quicho for the sharpest critique of the girl in all her more-than-human technosocial glory: the girl’s “ability to mutate inside the skin of an instantly recognisable form: these are not evidence of a powerless malleability, but rather an indomitable energy that might not be human after all.”[2] The Girl, through Quicho’s lens, perfectly understands cuteness as a behavioral code[3] and transgression as an act of deception.

Me vs the liberal girlhood they told me not to worry about

Where is our zoological Marx when we need him?[4]

But reader, I digress, I wanted to talk about a baby hippo: Moo Deng, regardless of her beatification into an icon of the revolution, is an animal in captivity, responding with force to attempts at domestication, literally biting the hand that feeds her. Sure, she is something of a sassy toddler, even if anthropomorphized into oblivion. But in a much sadder sense, she is a young animal waking up into the reality of her captured existence, responding to the prodding hands and boots with justified suspicion.

As tempting as it sounds, I think we don’t need another digression to a zoological reading of Marx to make the connection between the institution of zoos, public displays of wealth and power, and colonial trade.[5] Of course, the advancement of zoos is also linked to increased public learning initiatives as well as the growing movement of traditional conservation practices, but as good-intentioned as these might have been, they were (are) by no means immune to their imperialist substrate and its main imperative, to control and subjugate. In solidarity with the seemingly futile revolt of this young animal, I couldn't help but wonder. Does Moo Deng resonate so hard with the girlies because we all felt cute but trapped, and also wouldn't mind going a little feral?

Ferality tales

I've been fascinated with the idea of ferality for some time now. In the past decades, the entanglements of naturecultures have become increasingly visible in the sense that there’s theory and discourse around them, there are the davidabrams and the donnaharaways and the exhibitions and the critiques and the t-shirts and so on.[6] The practical magic of living-with has been very much active in many communities around the world. Anyway. Ferality is the act of resisting domestication, a gesture of transgression against the nature-culture divide. In order to be feral, one has to experience so-called civilization and then reject it, be it out of desire or necessity. As per Chessa Adsit-Morris: “What makes ferality such a powerful and useful conceptual tool is that it can operate on different scales and across different dimensions including acts, entities, relations, qualities, collectives, infrastructures, ecologies, and futures. As a process of de-domestication it signifies a move away from human-centric practices of control and domination, while also troubling the nature/culture divide in generative ways.”[7] I find intrigue exactly in these intersections: how this expression of negotiation between post-nature and post-culture interacts with the various facets of human experience and identity. The Moo Deng summer of 2024 followed the feral girl summer of 2022 (dare I say, a spiritual predecessor of brat summer), a most welcome trend of behavioral transgression in which online women celebrated a range of behaviors, from the uncanny to the unhinged. Feral ecologies, design, architecture, data, science—a myriad of disciplines craved a taste of the, well, undisciplined.

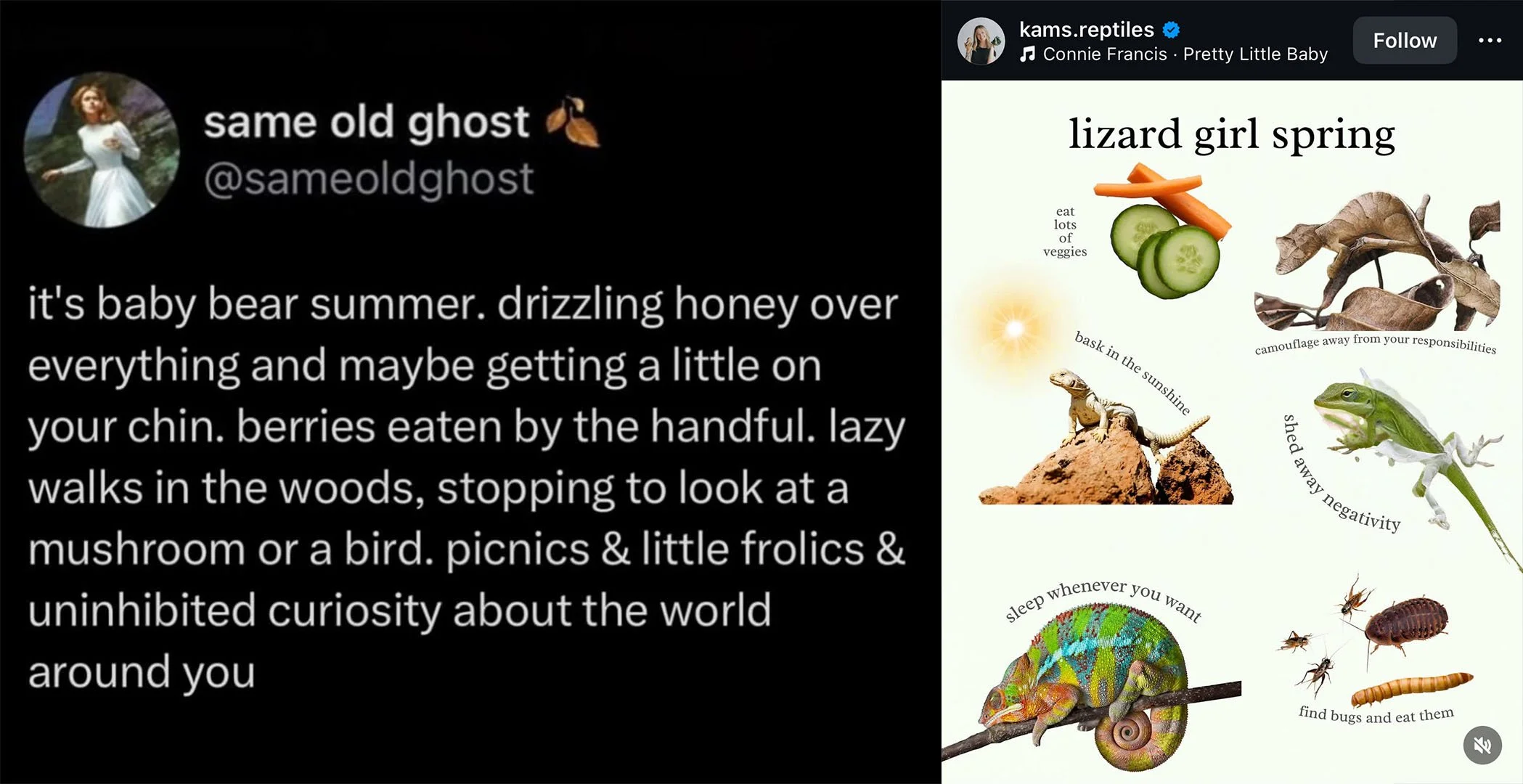

Get in loser, we are aestheticising the mundane. Left: @sameoldghost on Twitter (archival footage), right: @kams.reptiles on Instagram.

More-than⸺less-than

However, before we fully embrace feral ways, it’s good to recount how delegation to the sphere of non-human is not always, or even not often, a voluntary act and has, throughout history, been weaponized as a tool of abjection. I say ferality is a negotiation between naturecultures—between human and more-than—but more often than not, the negotiation takes place between human and less-than. Long before the Western knowledge apparatus invented a word for "speciesism," it held a pervasive belief that some animals are more equal than others. That is, even before the theory of evolution had put the human animal on a spectrum with other parts of the animal kingdom (and a kingdom it had to be in order to crown the human its ruler!), a hierarchy had been devised and enforced: those who are awarded full humanity, and those who lack it. Universal values, the great Enlightenment idea solidified in liberalism, are perhaps universalizing, but all-embracing they are not, and have not been imagined as such. In 1994, the same year Nelson Mandela became president of post-apartheid South Africa, the last human zoo was closed in France.[8] Let me say this again: the last human zoo was closed after the release of the film Free Willy (1993). Are we surprised?

Dehumanization—contested as the term itself might be, as it implies that the human is the only creature worthy of dignity—unfortunately, is not a relic of the nineties. I pick the most glaring current example: nearly two years ago, against the backdrop of the impossibly globalized, algorithm-hungry, unforgivingly instantaneous social media machine, the unlawful occupation of Palestine had shifted gears into an unprecedented, international-law-breaking massacre: a full-blown genocide. The language of the state-sanctioned Israeli media apparatus, one that had been until recently echoed by the majority of Western media, continues a sickening narrative strategy employed in the genocides of Indigenous peoples, in Nazi Germany against Jews, Roma, Sinti, LGBTQ+ people and people with disabilities, and unfortunately countless other mass murder events of recent history. Dehumanization in the sense of an assassination on life, dignity, and inherent worth, is a crucial part of this apparatus; be it in language (one rooted in racism and Islamophobia) or in scale—as slaughtering people by the thousands makes it cognitively and emotionally unbearable to mourn them as individuals.

A language of animalization is common to denote unworthiness, expendability, uncontrollability, threat of physical and sexual violence, savagery. Delegation to the sphere of nature, to wilderness[9], has been used to legitimize misogyny, anti-blackness, anti-Indigenous and anti-Roma racism, ableism, among other forms of ranking living beings with the aim of accumulating wealth and power. There is nothing “natural” about this, on the contrary—this story of white-supremacist capitalist patriarchy is so fucking absurd that it needs constant reaffirment through a myriad of cultural, political and economic strategies, from phrenology, eugenics, land dispossession, prohibiting language and cultural expression to billboards, insurance agency ads, motivational t-shirts, and monetized podcasts. However, other stories (I hope an expression of “other” will be forgiven at this point, as it has a point to make in its resistance to a language of modernity)[10] have always been manifest in the fissures of this system. Those are the ones that need reaffirming in order to crack it open. These stories need our strength, our “futile” scrolls through boycott lists, our clumsy and imperfect attempts at being good to each other.

Reader, I have another confession. The Moo Deng thing was more of a pattern than an exception. I tend to really fixate on things, fangirl is the word, stuff ranging from captivating narratives to handsome broody singers still obsess me to the point that seemed inappropriate past the age of thirteen. An agglomeration of Kate Bush posters, Hozier TikTok edits, and endless Star Trek trivia, I’ve long stopped feeling like being enamored with things is cringe. Now comes the part where I wince at myself—I truly believe good, captivating narratives can be perspective-altering, agents of change even, if I want to sound like an art foundation brochure. I really think other stories have a crucial role in cultivating a collective consciousness of mutual care. No, I don’t think our leftist reading circle/pottery club will necessarily overthrow capitalism. But I do think imagination is a crucial issue (here is the art foundation brochure again). I mean that in a very literal sense. Had I not experienced concrete expressions of “other” narratives, I am not sure I would have believed them possible either.

“Unfortunately, I am a racist.”

I am writing this with an emotional hangover of days spent as part of a community that felt truly grounded in reciprocity. Coming from the Climate Camp for Just Transformation, a movement-organized event spanning nearly a week, devised with the purpose of imagining the world otherwise. Organized by the Czech-based climate justice initiative Limity jsme my (‘we are the limits’), the camp, set in the Moravian-Silesian region of the Czech Republic, had two main focal points: to call out an unjust narrative (objecting to the building of a gigafactory as a sorry excuse for the idea of a just transformation of the former coal region), and to support and celebrate an aspirational one: protecting Bedřiška, a settlement in Ostrava, Czech Republic’s third largest city. Formerly infamous for its high crime rate and “problematic” inhabitants, over the past fifteen years, the residents of Bedřiška have transformed the community from a hotspot of social conflict into a network of mutual support and cohabitation of its Roma and non-Roma inhabitants.[11] A key moment in this transformation was an arson attempt in 2010[12]—an escalation of a conflict between neighbours—to which the community responded with a firm and deliberate declaration: the cycle of violence ends now.

“We go to work, we study, we pay rent, we help each other, we are the same as you.” Sign in Bedřiška, August 2025.

Three years before a Molotov cocktail flew through the window of one of the houses, another key moment of this story took place. In 2007, a recording from a public meeting of the housing department of the Mariánské Hory and Hulváky municipal district that took place in 2006 made rounds in the public and the media. On this recording, Liana Janáčková, the mayor of the municipal district, is heard openly admitting to her racism in no uncertain terms (“I don't agree with any kind of integration, unfortunately I am a racist”), and, along with her deputy Jiří Jezerský, alluded to various violent ways of getting rid of the Roma inhabitants with words I do not wish to repeat here.[13] As blood-curdling as it is, this is an important part of the story. These were the rancid conditions from which Bedřiška had risen, ones of overt racism, discrimination, and shameless rhetoric of subjugation against the Roma. This was the story that was told about them.

Bedřiška is a great story about a group of persevering people; it's a proud example of cohabitation of Roma and non-Roma residents that has succeeded without state intervention.[14] It is living proof how self-organized networks of genuine care and concern and a lot of patience can address the very roots of conflict. But resilient as it is, Bedřiška continuously battles smear campaigns and eviction orders, the latest extensive round of evictions taking place earlier this summer. For a certain group of people in power, it is unimaginable to invest time and resources into a thriving community[15], as the area of the settlement is seen by the local and state authorities as an opportunity for more lucrative buildings. It is unimaginable to protect people over profit. It is unimaginable to see this small, “insignificant” piece of land in the middle of the Czech Republic’s most polluted region for what it is: a community to protect, a story to tell, an intricate web of mutual care to look up to.

Ferality scales

What emerges at the intersection of various social and political struggles is, inevitably, that all bodies are not treated equally, even within that struggle. The Roma inhabitants of Bedřiška are denied the extension of their rental contract. The non-white protesters at pro-Palestinian protests are the first (or only) ones to get arrested, prosecuted, and at greater risk of physical harm and higher punishments. So, when we (when I) romanticize transgression, it is important to note that different bodies can afford different levels of ferality. Your behaviour within the dominant narrative will be evaluated and persecuted in close connection with the body you inhabit. The risks will be immensely larger for some. And yet (or precisely because of that) those bodies are often the ones most willing to take the risk, to suffer the discomfort.

I talk a lot about transgression, but the truth is—as I once tried to explain to my therapist —that I myself often feel like a shrimp without its shell, skinned raw. It’s unbearable, this feeling, and yet resisting it is fighting a fact of existence. But to say that all human beings display the same level of vulnerability would be trite. There are many material conditions and constellations influencing the amount of protective layers one can equip oneself with—all shrimp are equal, but some shrimp are more equal than others. I am not certain if shrimp would welcome the comparison, as they are concerned with completely different questions of violability. They might resent the fact that we refer to them in a collective noun, like undefined organic matter, not individual living beings. They also might not love that we harvest this “semi-living” mass with trawlers that kill them by the million, devastate their environment and disrupt aquatic communities.

But they are a fitting metaphor, as much of the so-called natural world is. Why so-called? Do you doubt the precipice between what is man*[16]-made and what is natural? Precisely, dear reader. There is no nature different from the one that constitutes you. Your humanity is not what separates you from so-called beast. It is what makes you part of all that is living.

The didactical premise of this text (as it is always good to explain your own jokes) has been, more or less, what can Moo Deng teach us about everyday resistance. The takeaway, however, was not intended to be that it's cute, but futile. What I hoped to convey is that discomfort with the cage is an expected and welcome feeling, even though resisting it often feels like toothlessly biting a rubber boot, useless at best and dangerous at worst. What I hoped to convey is that the cage is not a fact of existence; it's an artificial structure with great weight, but also with many, many cracks. Another world is possible, I want to echo, still starry-eyed from the promise of the past days spent between demonstrations, improvisation workshops, and communal meals, eager to pay the price of annoyance to keep this community, but I hold my breath lest I come across naive, too easily impressionable. Fuck it, I’ll say it.

Author update, 19.12.2025

Since the writing of this text, Bedřiška has faced another wave of repression. The community center’s lease has been terminated with no explanation. Several houses have been demolished and several inhabitants forced to move out. In November and December 2025, activists from all over the Czech Republic and beyond came to the site to support the community and block unjustified demolitions of houses that were proven to be in good condition. Among others, the demolition was also opposed by the president of the Czech Republic, Petr Pavel. Currently, Bedřiška is in need of international support and funds as more and more inhabitants are being forced out at the beginning of 2026. Follow the German-language Instagram profile @bedriska_ueberlebt to see more about how to support the community.

Notes

[1] Damnnn i dated myself with this one

[2] Alex Quicho. Girl Intelligence, p1.

[3] Ibid., p15.

[4] Donna Haraway. “Sharing Suffering” in: When Species Meet, 2007, p.72

[5] If you DO want to digress, you can start here.

[6] I say this as a proud member of the Haraway exhibitions cult!

[7] Chessa Adsit-Morris. “Liberatory Laboratories: a feral future for art-science collaborations” in Feral Labs, Node Book #2 Feralities, 2024, p. 16

[8] Bamboula’s Village, a fictionalized African village that featured 25 hired actors from Côte d'Ivoire to play a racist fantasy of the French colonizers, was an exhibit part of the Planète Sauvage zoo in Nantes, France. It is often quoted as the last human zoo in Europe and was finally closed in 1994. See more here and here.

[9] Wilderness/wildness is by no means a neutral term either – some complications of the concept can be found for example in Stacy Alaimo’s Undomesticated Land (2000) and Jack Halberstam’s Wild Things: The Disorder of Desire (2020).

[10] “Other” is an unpleasant, literally otherizing term. I hope the context of this text will make it clear I understand here “other” as in deviant from the hegemony of an artificially dominant narrative of profit over people; other as in intentionally different; other as having enough imagination to think of a world otherwise.

[11] Ondřej Kundra. “Chtějí jim vzít střechu nad hlavou, oni se jí nehodlají vzdát. Naději jim dodal i prezident.” Respekt.cz, August 2024.

[12] “Napětí v Bedřišce polevilo, domobrana nebude”. Denik.cz, March 2010.

[13] Both of them were taken to court for these statements. Jezerský was charged with defamation of a nation, ethnic group, race, and belief, and in June 2008, Jana Bochňáková, a judge at the District Court in Ostrava, ruled that although the act had taken place, it did not constitute a criminal offense. Liana Janáčková was protected by senatorial immunity, and the Senate did not hand her over for investigation and possible criminal prosecution because the senators considered the matter to be a special kind of political struggle. (Source: “Jsem rasistka, zní z pásky výrok senátorky Janáčkové,” Aktualne.cz, July 2007)

[14] Czech Climate Camp participants protest racism, fire hose used to spray-paint local authority brown, residents of condemned neighborhood distance themselves from such tactics. Romea.cz, August 2025.

[15] Ibid.

[16] [sic]

Katarina Rakušček is a cultural worker and storyteller-in-the-making. With a background in cultural production, academia, and creative writing, she currently works as Lead of Content & Narrative at TBA21, devising new narratives for an institution at the intersection of contemporary art and environmental advocacy. She is also a climate fighter, aspiring musician, devoted Trekkie, unskilled painter, and a believer in multitudes.