INTERVIEW WITH ADAM ENGLER

NUMEROLOGY, ACTIVISM, AND SOFT SCULPTURE

Conversation with nomadic artist caught in a place of stillness (or stagnation?) between return and departure.

-by Barbora Horská (Curator / Editor-in-chief of Improper Dose)

Your latest piece, The Measure of All Things, a site-specific installation for the Pohoda festival, uses the International System of Units to encourage viewers to reflect upon the concept of ‘right measure.’ It “[...] raises an urgent question: What is it like to live in a society with a double, triple, quadruple ... meter? And in general - who is the measure of all things?” (from the Artist Statement).

So what is it like for you to live in Slovakia, a country that slowly but with precision follows the direction of Hungary and Poland in terms of reproductive rights, LGBTQI+ rights, and migration policy?

For me personally, as someone who is sensitized ( by nature?) to various forms of discrimination, this is a daily struggle. We find ourselves in a stable instability and a considerable degree of exhausting confrontation with the environment. My level of frustration is compounded by the fact that I have had the opportunity, for which I am incredibly grateful, to try studying, working in other countries, and experience other standards. I understand that elsewhere it is not idyllic either and that there are different specific and identical problems everywhere. However, I sense a long-term degree of stagnation in areas that are key for Slovakia. I believe that one day Slovakia will be a country where it will be good to live, and I think that someone is living well today. However, my time is here and now. I try to make positive changes with my actions, but all that is left often is an aftertaste and a feeling of nothingness... And then the morning comes, and it all starts all over again...

Post-soviet countries have difficulty framing the socially-engaged art practices using western terminology. Particularly the term ‘political art’ can be highly problematic, as historically, it referred to art serving the system instead of the one addressing its issues.

Considering this, how do you define your own practice? Do you stick to the western framework, or are you considering Slovakia’s historical background when talking about it? Does the identity of your art change when presented home and abroad?

All art is, in a sense, political because it is created at a certain time in a certain place... This label can still work here and bring problems. I define my practice as engaged art, serving to improve the symptoms of today. I believe in the principles of democracy and realize that it can only work with a good education. In this case, it is necessary to be awake and aware of the system’s complexity and to choose means of expression that also reflect the historical context of the territory in which I work. If I subsequently present it in another country, different perceptions occur in the viewer, and the work, by relocating, acquires a new dimension. Context, always important, is what should be available here. It is fascinating to perceive the initial reactions to works that work with the socio-cultural code of one country exhibited in another country. It makes for a deeply enriching, educational experience.

Speaking of home, several of your artworks concern the issues of migration. What does ‘home’ mean to you in this context? Do you identify yourself as a Slovak artist? Do you make Slovak art? What would that even mean (to you)?

“Home is the hands on which you may weep.” (Miroslav Válek)

Home is where I feel free, and I want to stay there, without heaviness and constant confrontation with my surroundings. Maybe one day, I will find a home. Well, you could say that home for me was my backpack where I had everything I could fit in and everything I felt comfortable with. It’s hard to label a place that way, and it’s more like a feeling that everything is okay, at least for a while. My bag reflects, to some extent, the place I live in and try to function and work in. Certainly, I’m also influenced by where I grew up, so yes, I’m a Slovak artist, and I make art and obviously Slovak art...

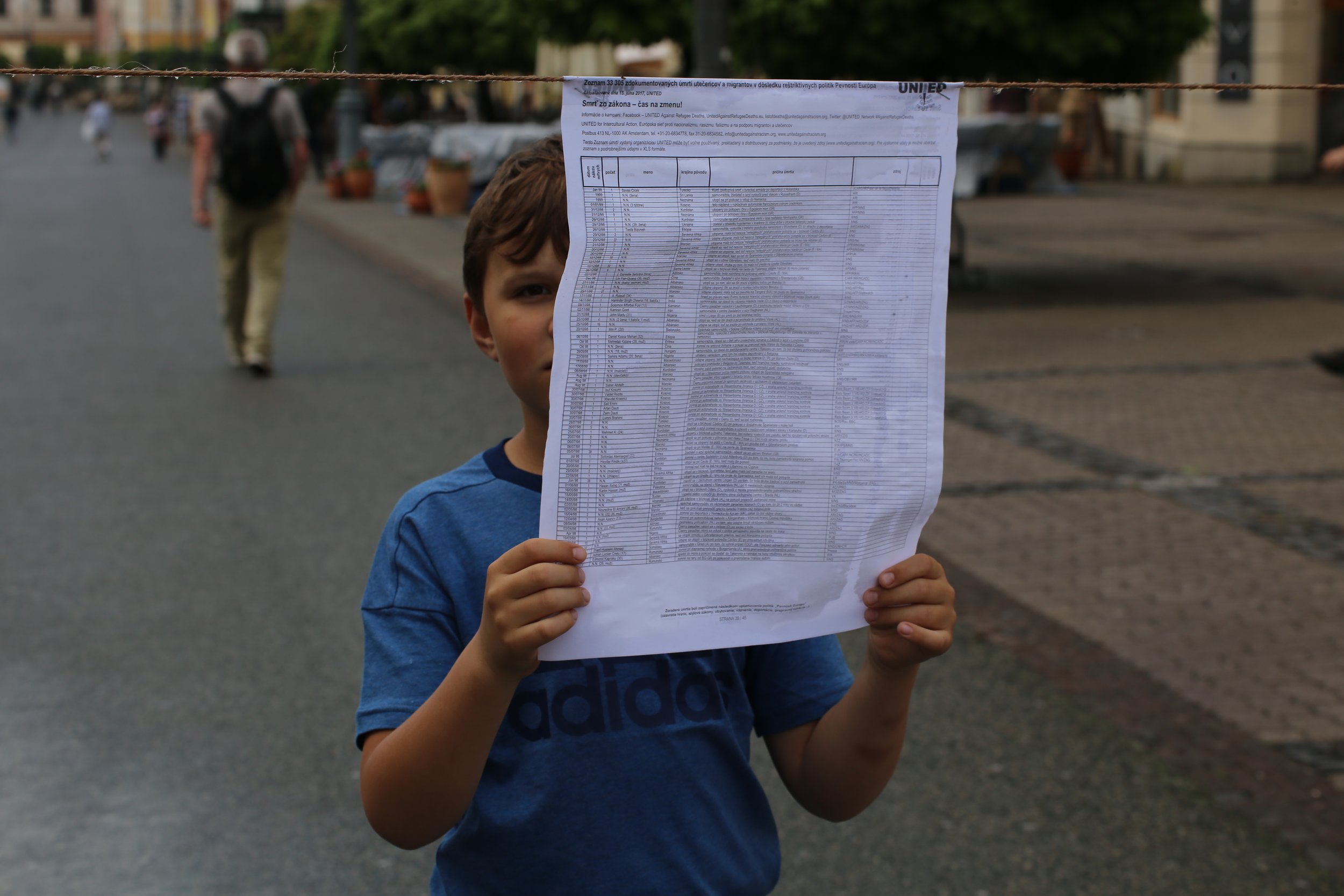

One of your public space interventions, called Freedom of Movement, in 2019 appropriated by Amnesty International Slovakia for the ‘Start the Change’ initiative, uncovered the lack of compassion toward migrants within the Slovak public.

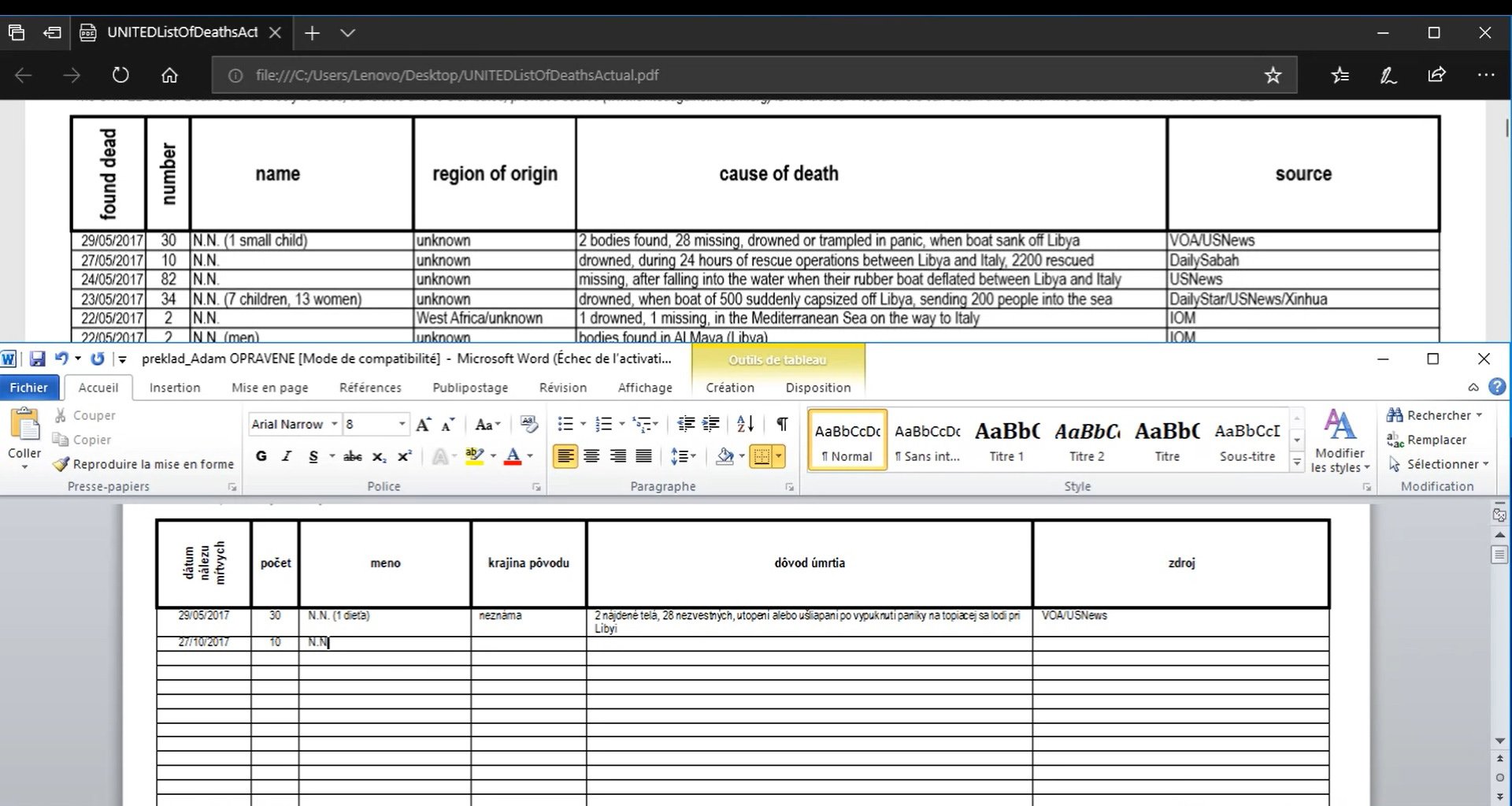

At the beginning of this project stands an uneasy performance of personally translating “Fortress Europe” The list of Deaths (of migrants and refugees trying to enter Europe since 1993) from English to Slovak. This 50 pages long document was then installed in the streets and squares of several cities across the country, creating a metaphorical ‘barrier’ in a way for people to stop and confront themselves with the reality of illegal border crossing.

Having the chance to document part of your tour with Amnesty, the responses of passers-by toward your installation were frankly chilling sometimes. How was it for you to interact with so much hostility and ignorance? And what impact do you think this experience had on the young people participating in the Start the Change project?

The first part alone, the translation from English to Slovak of the 50-page document with over 33,500 names and causes of death, was an incredible private event. It was often difficult to read and imagine all those lives needlessly and cruelly ended.

This project laid bare, the state of society, the hatred, and the impact of misinformation were on full display right on the streets. I have several hours of recordings of the biggest prejudices, slurs, and conspiracy theories. It was like standing directly under a post about migration on Facebook. It opened up different horizons for me.

Firstly, how easily society can be manipulated and how chillingly it can send a fictitious enemy to their death… Each of the interventions was held at both ends by young high school students who I spent an hour with at their school before mounting the interventions to prepare. They received information from Amnesty trainers, and we talked about the importance of the whole work. It was voluntary. I dare not estimate how many of those students went abroad to study... after this experience… On the other hand, I was glad that I had the opportunity to meet them, and I was pleasantly surprised by their personal opinions.

The intervention took place in five Slovak cities, most of the reactions were negative. However, I am grateful for every exception and the people who were willing to discuss, reflect, and open the space for empathy and new information. Many people came up and asked for solutions to their problems, and they started to express them. Unheard, frustrated people. For people who wanted to learn more, the intervention in the square was followed by discussions in local cultural centres with experts with lawyers and activists on migration and restrictive EU policies.

As an artist, do you feel the responsibility to address the current issues, or is it more about self-expression? Do you think the character of your art or topics you reflect on would be different if you lived in a more liberal country or weren’t part of a group whose rights are being constantly denied, questioned, and under attack?

I feel like a citizen who has been dissatisfied for a long time and is reacting or not reacting to current situations because even apparent deliberate inaction is a kind of reaction. I think that in my work, I often respond to the Slovak context, which is the territory in which I operate in some way. Still, at the same time, I consider myself a global citizen, and I am also touched by world issues, which I also have a deep need to reflect on in my work.

In this way, I also express myself. I am learning to take responsibility mainly for myself and my actions and reactions, even though I am not indifferent to the state of the world and current affairs and want to draw attention to it, perhaps idealistically. In some measure, I am still privileged and responsible for the state of affairs, always trying to help the one in need.

Whether I would create differently in a more liberal country, I think it would certainly change me first and foremost. I know from my own experience that whenever I have been in a country where there is equality, and you can really feel it, it was like breathing in at the top of my lungs for the first time and feeling the oxygen everywhere. At the same time, no matter how much it affects me, this is just one of the layers. I would certainly continue with my program and draw on my previous experiences. There are many issues in the world like gender equality, equality of opportunity, creating a safe environment, mental health, economic inequality, climate change, and there are some specifics everywhere. At the same time, everything is connected to everything. There is always something to tackle and new perspectives to bring. It’s always a challenge.

Another project, Family Pack, recently exhibited in Porto, addresses the position of LGBTQI+ families in Slovakia with a particular focus on the lack of their legal protection. It is also a personal journey toward forgiveness, depicting the inner struggle and everyday “fights” full of symbolism. Can you introduce the series of artworks it consists of and how your residency at OKNa expanded the whole project?

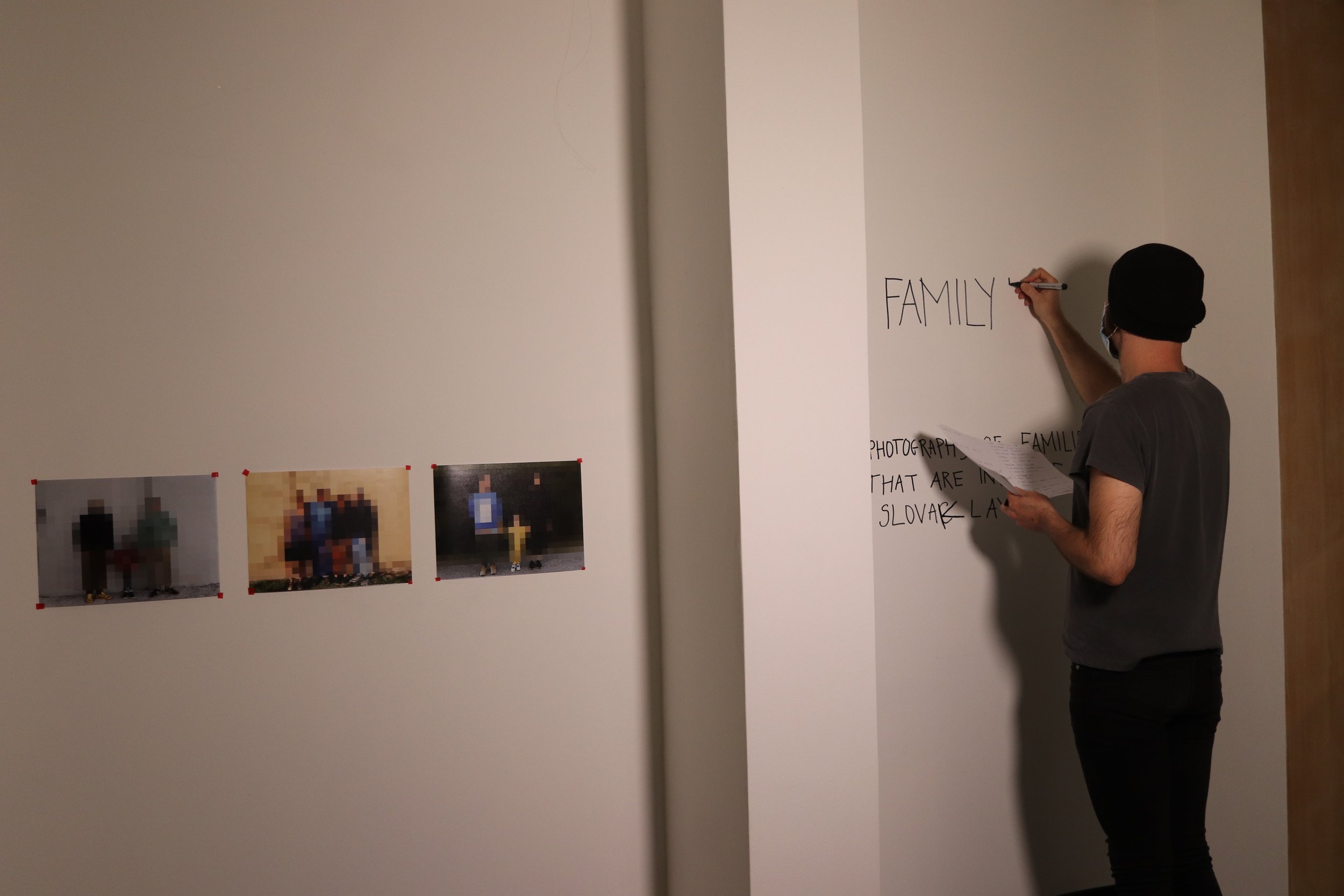

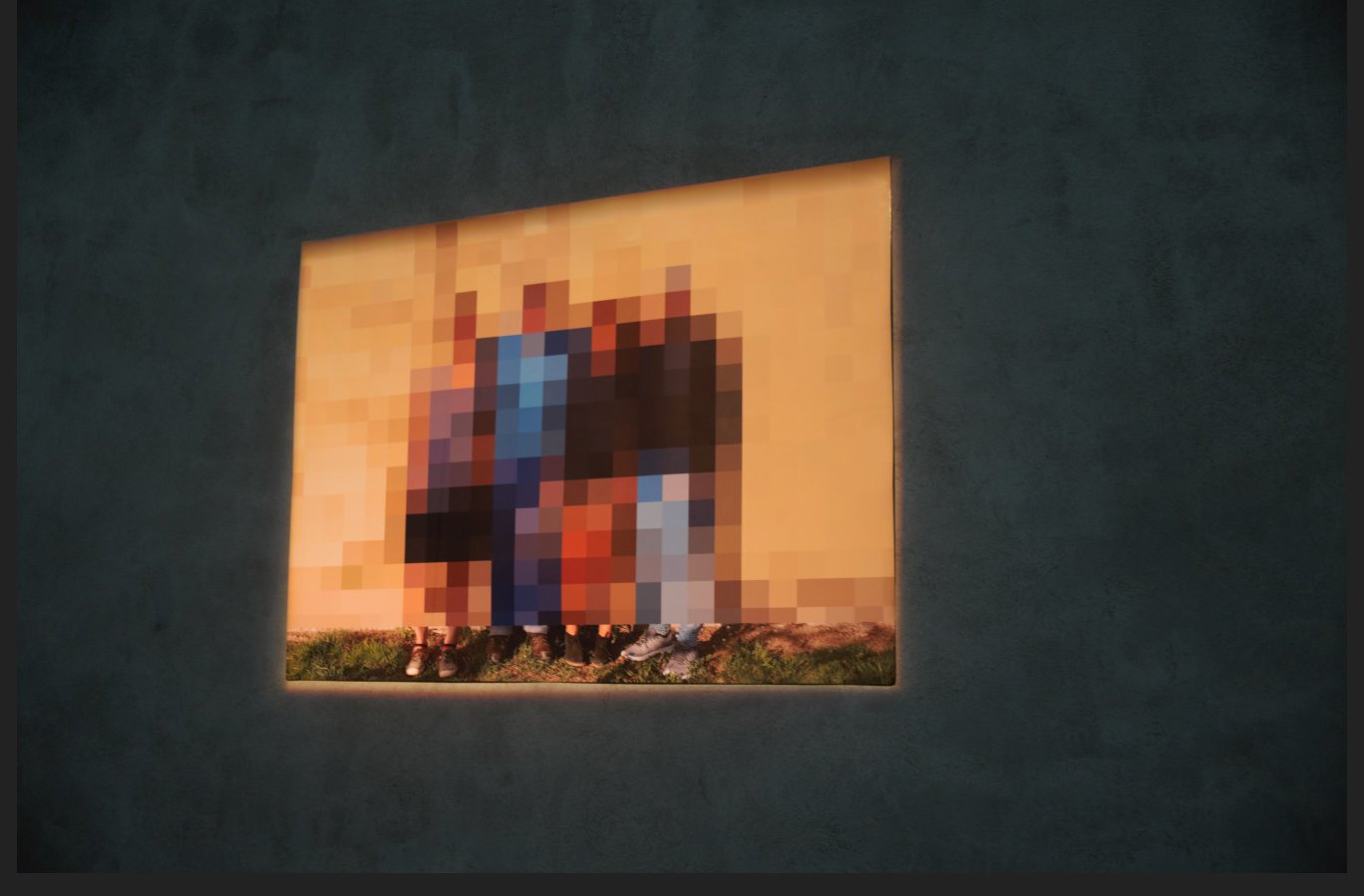

The Family Pack project was created in Slovakia in 2019/20 and was based on the realities faced by many families and individuals. The first part is a series of three photographs called Family View. I photographed authentic family group portraits of Slovak queer families. However, I did not receive their permission to publish their identities, which I further worked with and incorporated directly into the aesthetics of the photographs.

This fear of visibility stems directly from their previous negative life experiences. The algorithm I created is based on the real Family Law number 94, from 1963, which has not yet undergone a major transformation, changing the digital form of the photograph through an application that alters the recorded reality according to the number ninety-four I set up according to it.

The aforementioned law does not recognize forms of families other than heterosexual ones. Thus, this lack of legislation (in)directly modifies the reality of many families that are made up of persons of the same sex with their biological or adopted children. I have thus directly exploited the absence of visibility, through the visuality of digital pixels, through the filter. In this way, I want to draw attention and disturb the viewer, who this way can’t see a large part of the image. Or doesn't want to see? Here, it should be said that in the mid-2020s, an initiative of LGBTQI+ families in Slovakia has become visible and is taking steps on a societal and legislative level.

The next piece of the FAMILY PACK puzzle is Family Piece, 2020, an object designed for interaction. Here, I had a thousand-piece puzzle made from unedited raw selfie shots of families who were as well engaged in the project. Some families and couples refused to send photos. The reason was fear or a mode of concealment. These places and puzzle pieces remained white. Thus, the main intention of this installation is to allow the viewer, through the materialized metaphor of the puzzle, to get a glimpse of the individual families (puzzle pieces) and at the same time to give the possibility to piece together - to perceive the whole diversity of human families in this unifying manifestation. A profaned ideal into which we style ourselves and do not fit, which creates erroneous beliefs about our own inadequacy and non-acceptance by the majority of society, serves as a preimage according to which the picture of a thousand pieces of the puzzle is to be assembled.

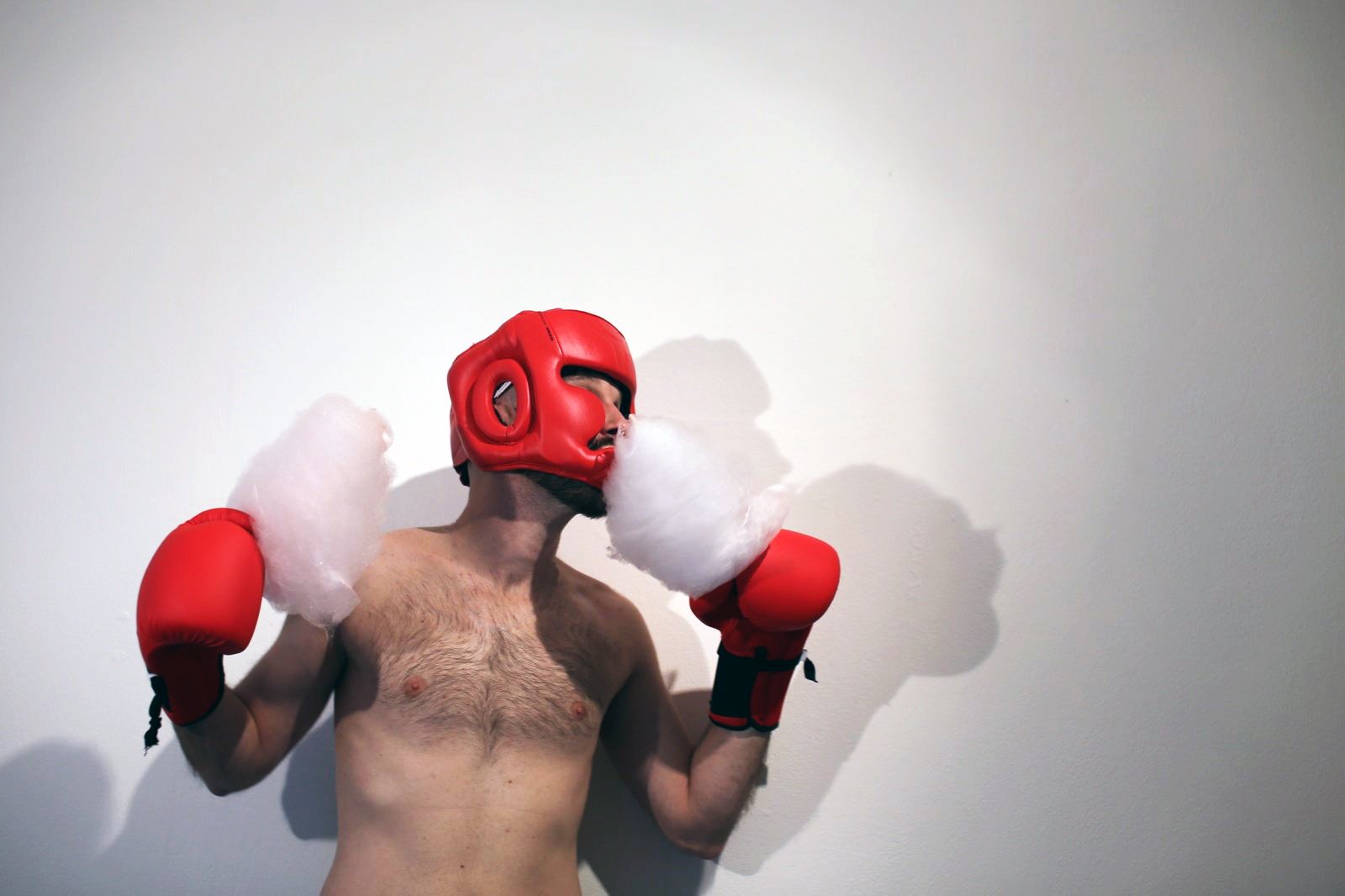

The next layer is Born this way? - a video performance 03:30 min where I am personally dressed in protective boxing gear designed for the ring. I convey the fight through these characters directly into the image. The helmet and the boxing gloves are as if fused with me, serving to protect me while at the same time preventing other activities that can't be done in them. I have been a boxer since birth, avoiding punches and giving punches. My body is thus directly fused with the gear, both protective and hindering. With punches, I try to imaginatively discard my own shadows and stigmas that I encounter in everyday life. To put all the anger and guilt out of myself. These stigmas are directly related to my sexual orientation and the almost completely heteronormative public space in which I live. You could say that it was a symbolic alter ego, a tired warrior. This self-reflexive, yet at the same time, universal video performance, however, begins sensitively and comically. It builds up to a sharp struggle with oneself over the immediate surroundings, moving into a momentary relief to a general weariness of these long battles. One could say that this is a symbolic alter ego, the weary warrior. On another level, it is a direct critique of such a pointlessly existing pretext for fighting, through self-reflection to a rethinking of the strategy of the fight itself.

The following video art, Danger Hot, is an ironic elaboration and a moment of awareness of the vicious circle in which LGBTQI+ citizens find themselves with the majority of society. The video is installed as one of two works in the medium of moving image with the original sound of sugar cracking and burning during cotton candy creation. The English title ‘danger hot’ is directly derived from the warning sign placed on the ring of the rotating turbine of the cotton candy machine. I have purchased the aforementioned machine for this purpose.

At the same time, the chosen name ironically thematizes the fear of this hot topic widely spread by conspirators. This ‘sweet vicious circle’ consists of misunderstandings and a lack of coming-outs since the majority then usually has no direct experience with an actual representative or representatives from these communities. Thus, people from LGBTIQ+ communities are afraid to come out about their orientation, but at the same time, if they do not do so, society will not know about them and will not start to accept them. According to the research, most prejudices are created out of ignorance, and the most effective way to break them down is through direct contact. Many and many hide their orientation from society and loved ones for years in fear of not being accepted. At the same time, however, the majority should create conditions in which each person can declare their emotional and sexual orientation without any problems according to their own feelings.

The last work from the Family Pack project is WE FORGIVE YOU (Odpúšťame Vám), a text object, 7x0,5 m. The cotton candy was used in my work for the first time as visual material. The decision for this material came from the research of the topic and a closer reflection on the concept and the graspability of the articulated idea. The intention of the object with the eponymous title in its textual Slovak version, We Forgive You, is to subversively convey the ironic subtext of these words from a material that is sweet, pleasing, and empty... / Forgiveness is permissible in the sense of forgiving those who are influenced by the aggressive propaganda of the anti-LGBTQI+ especially in their own interest and to pay attention to the propagators of this hateful purposeful rhetoric./

Regarding the exhibition in Okna, we decided to display the Family Pack media installation in agreement with the director of Radu Sticlea. We found it interesting to present these facts in a European country where the situation of equal rights for LGBQI+ people has been positively addressed.

At the same time, it could also serve as a reminder that even the gained can be quickly lost and what it looks like in other parts of the EU. In the same way, I also included a video not yet presented in Slovakia, in which I try to taste the sweetness of cotton candy, but I can't do it because of the helmet and gloves. In this respect, I consider the inclusion of the video to be positive, as it directly demonstrates the daily stigma that I have been slowly shedding even after a long time away from Slovakia and which I started to realize right on the spot.

I think that this project and its presentation in OKNa showed the state of the eastern member of the European Union and how insensitive it is to LGBTQI+ people even today. The audience's reactions were in the spirit of compassion and newly found awareness. We also included in the exhibition some of the work I worked on in Portugal as a part of the presentation of the residency outcomes.

The works were cross-cutting material and thus expanded the exhibition to include the theme of self-determination and toxic nationalism through photography and video performance and the object. These works, or rather situations, were meant to finish my presence in the space of the OKNa and how the new environment affected me.

Regardless of the topic, the range of techniques you’re using is quite broad and diverse. However, what stands out for me is the layer of numerology and divination practices like tarot that you sometimes incorporate into your work. I know this interest goes beyond art concepts and is an authentic part of your life. Can you tell us more about it? How did you come to this, why did it resonate so strongly you decided to use it to address both political and personal issues?

Not all phenomena and things can be explained in an exact way. Nevertheless, even energies can now be measured, which is the subject of quantum physics. My personal interest in numerology is rooted in a simple desire to understand myself. Which, to some extent, has been successful since we are not set in stone. I am trying to uncover and move forward - an endless journey of self-discovery, self-awareness, and transformation.

For me, Tarot means a different perspective on the present situation I find myself in. Each card has its own theme, and I think it also says a lot about imagery and the ability to detach on personal levels. It can also be a source of inspiration. Ultimately, I am the one who makes the decisions and bears the responsibility... But here we are again at the beginning : who am I, ME ?

Could this acknowledgment of existence beyond the material world be a way to cope with everything happening around us? Do you have other mechanisms to avoid complete despair?

I certainly believe in some form of an immaterial world, just as I believe in a material world. It's just that invisibility but at the same time a certain sense of interconnectedness. Everything has always started as an idea, a utopia. In a sense, numerical signs and meanings help me to discover and transcend myself. I don't have other mechanisms, and I'm always looking for them. Maybe the desire to search, discover, and not slip into a long-term lethargy is my strategy not to succumb to despair. It's not always easy.

Nevertheless, I am sensitive to it, I reflect on it, and I look for a way to process despair as well or to tame it. I see the creation and research process as a form of conveying a vision to those around me. In a way, it's something that makes sense to me.

What are your next plans?

I'm currently sorting out my moving options, and everything is in the process of being resolved. I have been living in Slovakia for the last six months. After co-organizing PRIDE BB and an exhibition at Pohoda Festival, I am working on experimental graphics and freely exploring the theme of trust in the medium of video and object. At the same time, I am participating in the project "SKARTCITY for Creativity in Schools and Public Spaces" under the guidance of lecturers from the Prague-based organization Society for Creativity in Education. Together with our partners from the organization Škograd from Belgrade, we are working on the development of a methodology for creative education in public space that connects the world of artists, educators, and cultural managers. Shortly, we aim to enable students to develop competencies for the 21st-century world and at the same time to be responsible citizens.

Adam Engler (1990, SK) received his Bachelor's degree in the studio of Soft Sculpture and his Master's degree in the studio of Photomedium at the Academy of Arts in Banská Bystrica (SK). He has participated in several exchanges and artist residencies in the Czech Republic, Romania, Portugal, the USA, and elsewhere. He focuses on performance art, artivist projects, unconventional material actions, text, and visuality in the field of collapsed media. His productions refer to themes such as migration, gender diversity, and intersectionality with overlaps to engaged art, human rights, social and environmental justice.