TOUGHEST LOVE

– by Eva Balayan

How I reincarnated but kept the memories from my past life.

I remember my grandmother having a small booklet with many numbers and dates. You could look up the year you were born and find out who you were in your previous life. The funny thing, the book would say the same thing to everyone who was born in the same year. I was very young and believed in it. Of course, I tried to remember how that was and if I could make any sense of this. This memory came back to me as I realised that I was living a life with memories so far; they could be someone else’s.

When I was 15, my mother packed my brother and me and ran away from my hometown Yerevan. We were suddenly immigrants in Austria. It was a tough life, but I did not perceive it as hard and disrespectful as many others experienced it. I remember people being very nice, approachable and helpful. My brother and I both spoke English and did not fall into the category of “unrelatable foreigners”. We quickly started learning the language, finding friends and growing together with the new surroundings and its new problems that were way more attractive and easy than the ones we used to face. Anything that was linked to my old self I tried to make as distant as possible.

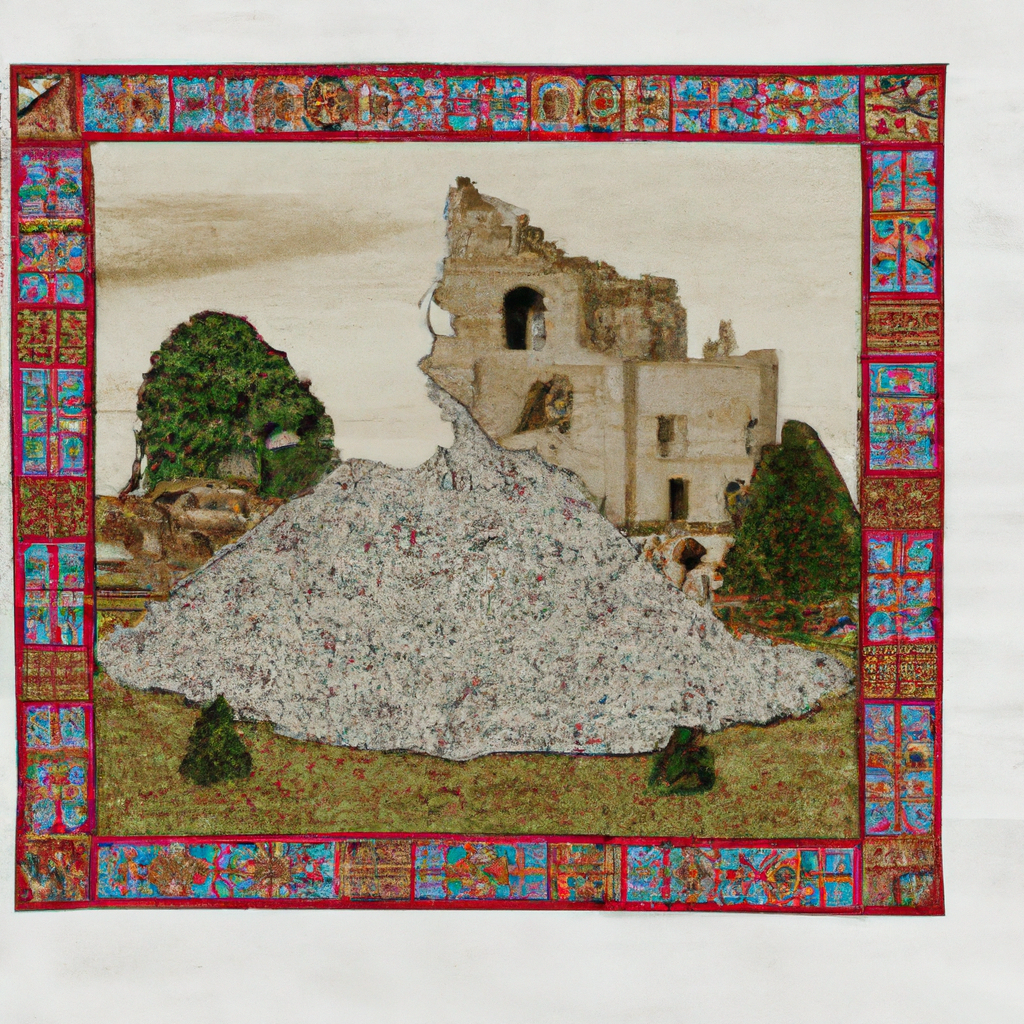

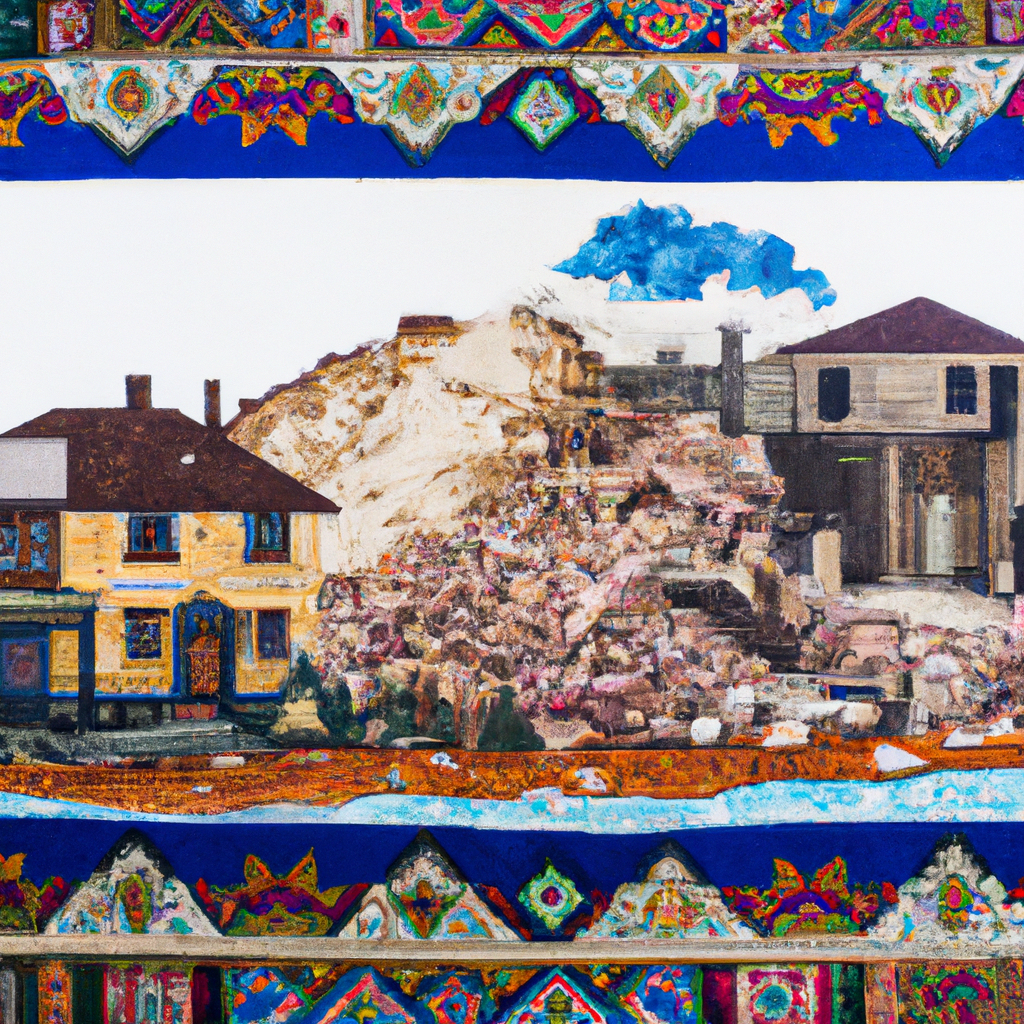

After years of oblivion, I had an extremely short trip to Georgia, which is the neighbouring country to Armenia. Since I still have my refugee status, I cannot travel to Armenia, and I have never seen my hometown since I left it. Technically I could go back, but this would be self-destructive and stupid. The smell of the air, nature and people in Georgia gave me an immediate and strong flashback. I had tears in my eyes and a bleeding heart. I started having dreams about going back: those were happy dreams with background anxiety about issues returning to Austria. Throughout the years, the call in my mind got louder and louder. With the current war situation that is happening between Armenia and Azerbaijan, anxiety developed — the fear that in just a short time, my country will be eliminated and no one will ever remember. First I started collecting Google images I found that were valuable to me, and then I started drawing and sketching the memories of my childhood. With the AI thing happening, I decided to give it a try and see what it would do with my memories. I would like to share some of the experiments I have done.

My past self used to have a constant feeling of being in trouble. It does not matter how obedient you are; there will always be someone who will be pissed off by you and make you feel guilty. Guilt is a widespread feeling in the society I grew up in. It’s so weird to experience that my Austrian friends and colleagues don’t quite understand some of my patterns. I tend to ask myself where did all this guilt come from. But when I stay alone and start digging into myself, remembering what kind of a feeling I used to have going to school or seeing my grandma or just walking with my friends in the yard: someone will be unhappy with you and won’t hesitate to make sure you know they don’t like what you do.

When I lived in Yerevan, we used to move a lot. The first time was because of the war and collapse of the USSR in 1991. It was the year I was born and the whole country had no electricity, food or heating. Many families moved together to make it easier to survive. Later we moved because in the house I was living in, we had problems with sewing pipes freezing in winter, and the simple process of relieving yourself could end up disgustingly for everyone in the flat. The first time we moved, it was to a friend who was living in the city centre in a house that was built in the 19th century. Back in the day, those houses were the main attraction of the capital: old, beautiful stone buildings with complex stone cuttings and wooden balconies. When spring came, we went back home. Our friend died. The government came up with a project to tear down all those old houses and build new ones. That was a terrible idea. Getting rid of the historical part of Yerevan instead of cleaning and restoring it was not just sad but also stupid and irresponsible. The new houses were heavy and tall for that seismic area with groundwater and aesthetically looked very dull.

In a couple of years, the same problem happened. We moved out, and this time we moved into one of those new buildings together with my stepfather. It was the first and only house from that project.

Living there was absurd: as if we were in a different city. Besides the security on the ground floor, a proper, always functional, clean elevator and tidy staircase, it was weird to look out of the balcony and see wide empty spaces with pieces of demolished old buildings around.

The government promised to reproduce the old houses in a new area, but that never happened.

The apartment where my family used to live was in a distant district in Yerevan. It was a soviet project, and when it collapsed, some houses in that district were never finished. Those were building blocks with 16 floors placed in rows that should form the Russian letters of the USSR from the plane perspective. Our building was, fortunately, one of the ones that were complete, but they were never properly taken care of. After some earthquakes, every apartment had cracks in the holes, and mice would spread in the building. We got a cat, and after that, the mice attacks stopped forever. The elevator was not functioning quite often and walking 16 floors in total darkness was a normal thing, even for the oldest people. Still, I remember the building being like a big family. Each circle of a letter would be called a chain and parents would forbid kids to play with other kids from different chains. Neighbors liked or hated each other, while their kids would fall in love, marry and make new families. It was like a big anthill.

Despite the electricity going on and off, there was also a thing with water. Twice a day for one hour, we could fill big buckets for later use and wash the dishes from the tape. Sometimes if water was not “given” for days, people would go down and fill the buckets from the pulpulak — a stone that is traditionally placed on the street or at the entrance to a building, with fresh drinking water constantly flowing out of it. Some parents would go themselves, some would send their kids. It was great fun to stand there, wait until it was your turn, then press the stream with your thumb to make it go into the bucket and when it was full, walk all the way up the stairs.

Besides cemeteries and horses, I mostly enjoyed seeing the huge absurd house on the top of the hill that belonged to some criminal oligarch dude whose name was Dodi Gago. The fascination with that scene was that it was taken out of any concept: Roman columns, statues, fountains and an English garden. I also remember a big lion in front of it. Dodi Gago used to have a gas station right on the corner of the road with another lion as a logo. The houses and villages around it were normal. Regular people living there and striving while this huge absurd building was jabbing you right in the eye with its opulence and cringe.

One day we were driving back home from lake Sevan. We were on some rural road and had to wait until the sheep passed. There was a car parked on the side and from first sight, there was nothing special about it until we saw the passengers: two men and a thin, grown-up cow in the back seat.

The memories I have are already 16 years old. I have spent the bigger part of my life away from Armenia and neither the people I used to know are there, nor their houses. The city and the entire country have changed. When I was little there were many cranes and storks with their nests on the top of country houses and on every cable line pillar. Storks are a symbol of happiness and for every house, it was a great joy to have a stork nest on its roof. You could see so many when driving outside of town. In the last years of my life in Armenia, there were not many of them anymore. The storks flying away is a symbol of so many people leaving the country, just like myself.

Eva Balayan is a media artist based in Vienna, Austria. Her main instruments are rooted in digital art, illustration, performance and sculpture. Her works are focused on the interposition of digital and analog techniques. The main topics of her art practice are post-humanist identity, consciousness, as well as tradition and culture, while she tries to juxtapose perception of reality with transcendence. Currently, she is a student at the University of Applied Arts, Vienna.