INTERVIEW WITH KSENIA YURKOVA

-by Justina Špeirokaité (Curator at Improper Walls)

My personal interest about the cultural scene in Russia and how it is influenced by politics, was growing for some time, especially after the last summer events in Belarus. And although Belarus and Russia are countries neighboring my home land Lithuania, I realise I know almost nothing of what art and culture breath there.

To find out more, I decided to talk to Ksenia Yurkova, a curator and artist, who recently moved to Austria, and can tell us more about it based on her own experiences.

I have a pleasure to meet Ksenia through the QUESTION ME & ANSWER initiative, in which she’s taking part. Her artwork, together with Ramiro Wong, you can view at Aa Collections (Reindorfgasse 9) until the 6th of March and virtually.

Who is Ksenia Yurkova? Could you please briefly tell me about your work and life between Austria and Russia?

I am an artist, curator, and researcher, living between Russia and Austria. A long time ago I was trained as a political journalist, I even started a PhD in the field of communication theory at St. Petersburg State University. Quite early I realised I could no longer pursue any independent study as censorship has stood at the head of the research process. It started one day after law enforcement officers brutally crushed my dean’s office. I left the program in 2010; since then I have worked as a cultural journalist, then as an art critic, then I started to organise cultural events and finally became an exhibition director of a big venue in St. Petersburg – Tkachi (The Weavers). However, this collaboration also ended up misfortunately. The owners of the exhibition centre illegitimately broke a contract with my team and literally kicked us out after we had launched a notorious exhibition concerning religion – I admit, it was a rather frivolous choice at that time, when St. Petersburg was led by an ultra-orthodox governor. To freshen up the context: The Pussy Riot’s court case started in 2012 and created a precedent to prosecute people, especially artists. According to a new Blasphemy Law, in Russian transcription the bill proposed prison sentences for "public actions" that "clearly disrespect society" and are aimed at "insulting believers' religious feelings”. The bill was accepted on the 11th of June 2013; exactly by this time, the exhibition centre stopped its work under my direction. After that mishap, my team faced three trials, officially referred to as economic affairs, but no-doubt having a political rationale. We couldn’t remain unpunished for publishing the open letter to the governor in which I invited him to come and check any extremism on the show himself. After the exhibition had closed, its main curator had to flee the country. A long time after I couldn't find any work in St. Petersburg and in a couple of years I moved to Helsinki to get my second Master’s degree, this time in art.

In Helsinki, together with several artists, I launched a Festival-Laboratory Suoja/ Shelter which last summer lived through its third iteration. A little more than one year ago, after I moved to Austria, together with my partner, Austrian artist and curator Martin Breindl, I launched an artistic research laboratory InSilo (Hollabrunn, Austria). One branch is supposed to be an artist-in-residency programme oriented on the showcasing of the underrepresented artists, and the other branch is an emergency project for artists suffering any kind of political persecutions in their home countries. For the latter part, we collaborate with the international Artists at Risk network.

As an artist, I work with text, photography, video, and installation. Lately, I am researching the phenomenon of affect situated within a political body. I focus upon how a stage of individual perception, to which one can relate memory, traumatic recollection, and problems of identity construction, transforms itself into effects of collective resistance. Sometimes I do some self-reflective works, for example, in the group show within the Question Me & Answer project, I am reflecting about the conditions of artistic labour, and at the moment gathering some statistics about current artistic incomes – the data which works as a reality check to those who prefer to impose some romantic views on the artistic work.

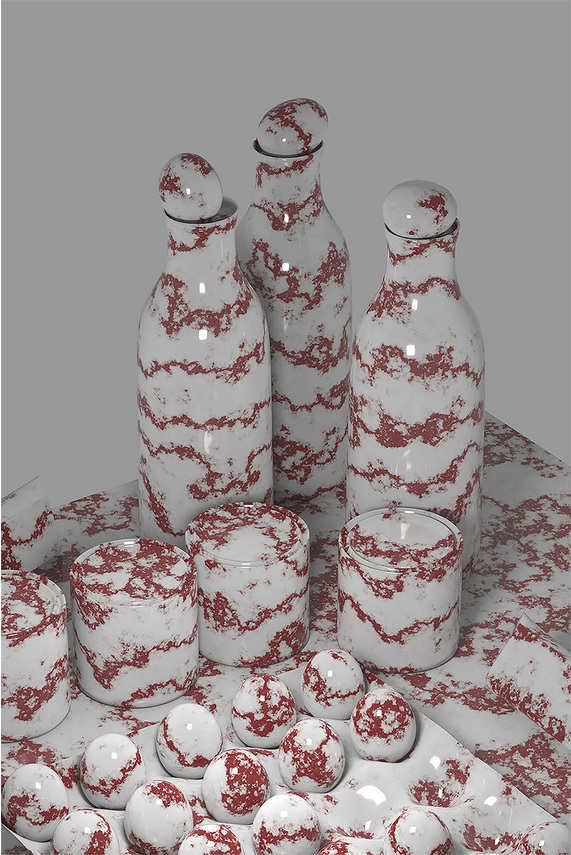

© Ksenia Yurkova

One of my favorite bands Molchat Doma is not allowed to play in their hometown Minsk, and Shortparis, from Sankt Petersburg, refuses to talk about their music from a political point of view. On the other hand, we all follow the long-time fight of Pussy Riot and the more recent one of Ic3peak. How much are artists risking openly expressing political critique?

It is funny to act as a Kulturträger of Russian music since I do not have any profound expertise in it. For this, I needed to consult with my almost 18-years old son. Then, after listening to hours and hours of tracks he provided, of which I was partly already familiar since they became the anthem of protest, I can say the following. In my humble opinion, the Pussy Riot these days (mainly I am speaking about Tolokonnikova) has become a commercial project exploiting the kitschy representation of state violence horrors. This is obviously neglected by the younger generation, just for lacking the right vibe, read: for not certainly satisfying quality. Shortparis is a bit of an enigma, but I assume that they also tend to be a commercial undertaking. Rather talented (even if the general aesthetics and the image of their frontman are appropriated from a protagonist of Zsolt Nagy in a movie by Philippe Grandrieux A New Life (La Vie nouvelle) from 2002), but taking political contexts more pragmatically than sincerely. I presume they are truly successful in trading the obscure frenzied Slavic spirit to the Western public (in other words: trading back to the West the colonial French gaze on exotic Eastern Europe).

You are right about Ic3peak, they are some sort of role model for teenagers and young adults. The most noticeable projects like Kasta, Husky (with the most radical lyrics), Noize MC, Anacondaz, and Oxxxymiron – are regarded to be the voice of a current political protest. I am afraid, though, most of them are still cherishing their misogyny and explicit masculine imagery.

To answer your question about risking: most of them faced bans on the concerts. Some were detained or even arrested. Noize MC was arrested in 2010 for 10 days due to the insult of the police in his texts. His numerous concerts were banned during the past decade, but he still lives and works in Russia, not leaving in principle. Husky was arrested in 2018 for 12 days: he decided to organize his concert unofficially after he received an official ban to perform. Since that time, his lyrics became even more radical, and his album «Хошхоног» (Khoshkhonog), which was released in 2020 deals directly with political issues, including the presidency of Vladimir Putin. I am not sure if Husky still lives in Russia, though. I cannot name feminist collectives openly who are protesting or manifesting their political views. Maybe Ic3peak, or partially it can be AIGEL. But once again – I am not a big expert.

Personally, I find music as easier access to the Russian art world. However, I have had the pleasure of working with a few visual artists and also following a bunch of others on social media. But I would like to ask you, which artists from Russia and Belarus would you mention as influential and a must follow?

This is a broad question, I reckon I will need to narrow it down to those artists and projects which exist in the focus of my attention and which I personally find worth a follow.

I have already started to talk about political/censored/persecuted art, thus I cannot help but mentioning the projects dealing with feminist issues in the first place, since the movement is experiencing some sort of new Renaissance, and not only in Russia. In the Eastern European context we face a huge women’s uprising in Belarus and Poland where it has become an objective hazard to the conservative regimes.

Returning to art: context-wise, I cannot avoid mentioning two iterations of The Feminist Pencil, The Feminist Pencil 2 (2012-2013) – projects that showcased women's graphic art, curated by Victoria Lomasko and Nadia Plungian. The name of Lomasko might be familiar to you – her mural Underwater (2020) could be seen in the exhibition “… of bread, wine, cars, security and peace” in Kunsthalle Wien. Unfortunately, from what I can see scrolling the web pages, not much of the documentation is translated from Russian, therefore if you are interested in the artists, I recommend you hunt them with the help of the Google Translator and image search. Needless to say, not even ten years ago these two events caused an avalanche of criticism from the audience and from the ‘established’ art-institutions. During the last decade more and more artists, projects and collectives are appearing, dissolving, reestablishing, cooperating and reincarnating. To give you some insights: these are different flexible and fluid groups connected with the Cyberfeminism digital platform; artists and activists around DK Rosa Cultural Organization; «Ф-письмо» (F-Writing) – an independent research project dedicated to feminist, gender and queer studies; a constantly growing collective ShShSh, comprising about 30 female artists; the Feminist Translocalities – a digital portal, zine, and a ‘matrix of feminist pasts, presents and futures’ – just to name a few.

The majority of the aforementioned groups are self-organised created to confront the 'established' and self-proclaimed 'high-brow' art- enterprises in Russia. Sometimes it is both amusing and distressing to observe how the discourse of resistance is consumed and exploited by some major oligarch-financed private entities, e.g. the Garage Museum, which recently collected a bunch of independent groups under one umbrella exhibition about care. Or quoting the official website, ‘humanitarian mission to help the arts community’, this immaculate gesture inspired me to make a critical piece; I was not surprised for even a second that my work hasn’t been chosen. You can make your day by reading the proposal here.

My personal preferences partly coincide with the participants of the Suoja/ Shelter Festival-Laboratory which I have been organizing and curating for three years. Just to mention several from Russia and Belarus: eeefff, Rabota, zh v yu, Practical Affectology Unit, Aliaxey Talstou. Apart from that, I can recommend following those with whom I once would like to work, for instance, the League of Tenders – an imaginary organization based in Krasnodar, Sever-7– a research base from St. Petersburg;micro-art-group Gorod Ustinov from Izhevsk, which I personally like for the concept of non-place; and many-many more.

I heard that as a consequence of the non-democratic government control, there’s a huge underground scene in Russia. Is it true? Could you tell me a bit more about it?

To extend an answer to your previous question. The term 'underground' has already lost its original meaning. Artists from Russia can simultaneously self-organise, be commissioned by some state-affiliated institutions and be present in the international context. Essentially, if they are witty enough to arrange it by themselves. Another problem – there is not such a thing as a clearly functioning system, a social lift for artists. Nothing guarantees you a minimum wage (more than 70 per cent of artists have another employment), and no one has any clear understanding of which topics or themes you can touch and of which you cannot. It may appear a bit schizophrenic: a big institution allows you to show something bald, and a small gallery starts to censor just for the sake of a precautionary measure. Agree – what a wholesome strategy to impose insecurity – to obscure what is forbidden, and what is not.

Another tendency I have marked: many artists prefer to become cryptic. They operate with on one hand fashionable topics like speculative materialism, posthumanism, etc., on the other hand, it keeps them in a safe zone: since their practice is not directly confronting state, religion, human rights, and official historiography – officials can turn a blind eye. For this reason, I drew your attention to feminist art – it becomes riskier and riskier to produce it as it bothers the stability of all kinds of sacred clams.

The international artist community seems to be aware of what is happening, but the participation in supporting the anti-government movements I find vague. How important is the involvement of the art scene in the events in Russia and Belarus?

My answer can be very brief. This human's right disaster that happened in Belarus lately was on the large scale overlooked not only by artistic or cultural communities – neglected by European citizens and governments in total. This is something happening in front of their eyes, not in some remote places. This I find embarrassing.

How are artists getting involved? In Russia, Belarus and outside? And how can I get involved?

I am happy to witness that in Belarus, as well as in Russia, the civil society starts to self-organise, create temporary non-hierarchical communities which fundraise, collect food and clothes, deliver goods to the detained or inmates, doing some communicative or layered work. Mainly using sporadically appearing Telegram groups. The artists, especially feminist artists are very active and efficient in this. It is hard to distinguish the cause and reason, but I see more and more violence against women artists. The most outrageous cases are the trial against Julia Tsvetkova for the depicting of the female body (here you can find information in English and share – the case is still very important to highlight). This year, the artist Daria Apakhonchich was labelled as a 'foreign agent’. Artist Daria Serenko is receiving life threats after organizing activist events; artist Katrin Nenasheva is constantly watched by law enforcement agents, this list can be continued.

In Belarus artists, journalists, cultural workers are facing unprecedented force: artist Uladzimir Hramovich was arrested recently; journalists Catarina Andreeva and Darya Chultsova imprisoned; artist Yuliy Iljushenko, philosopher Olga Shparaga, artist Nadya Sayapina, photographer Julia Volchok, and many others were arrested and/or tortured in the detainment centres.

There are many ways to help. It is rather easy to Google solidarity funds and to spend a few minutes to check if they are trustworthy. The best way to support artists – is to buy their art. You can promote them, spread the word, organize an exhibition, but the most important is to provide the artists with the means to defend themselves and sustain their dignity and creative sovereignty. If you are an organization – you can organize auctions, off- or online. This, for instance, is how Stedelijk Museum supported Yulia Tsvetkova. Unfortunately, not a single serious art-collector in Russia hasn’t acquired her work.

Maybe to convince you, I will bring some statistics from the small research I made in the frame of the Portfolio Performance piece, I have opened recently in the Aa-collections gallery in Vienna together with artist Ramiro Wong.

These are figures of artistic income in Russia. As you can see, more than half of the respondents earn from 0 to 300 Euros per year.

To compare, the average income of artists in Austria is 5600 Euros per year (this sum is required, for instance, to have an artist’s social insurance).[1]

Part of the means from the sold artworks you will redirect to NGOs helping political prisoners in Belarus and Russia. What can we find at your online shop?

That is true. I am trying to work in several directions to support my artistic colleagues. As an artist and an individual – by selling my own work and donating part of the income to the NGO’s, or directly to one who needs help. I sell the original works which have been exhibited worldwide, as well as limited prints. I am extending the assortment all the time; but one can also check my website and choose some artwork that can be produced individually. Or photographic work.

Another direction is my work in the frames of the aforementioned InSilo Project. As a curator, I acquire artistic work for the residency, and at the moment I’m preparing a plan to promote and sell artistic works of the invited or fellow artists. As InSilo acts as an NGO, we do not plan to make a profit out of these kind of sales.

And the last project to mention – the Patreon page of the Emergency Project AIR InSilo. You can donate any sum so we can invite artists suffering political persecutions or censorship to Austria – to work and rest for three months.

![To compare, the average income of artists in Austria is 5600 Euros per year (this sum is required, for instance, to have an artist’s social insurance).[1]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/58346c38bebafbb1e66cce65/1614523455523-WTIP0QLUWZXI27KDCEUO/Screenshot+2021-02-28+at+15.44.03.png)